Doi Pangkhon

After two weeks at a meditation retreat in a nearby village, Kel & I suddenly shifted into “go mode,” joining our friends from Vietnam on a whirlwind coffee farm tour. The retreat was just what I needed, a good recharge of the mental batteries and inspiration for self-care in the coming year. Here’s to hoping I can maintain a little bit of my “retreat self” for the next 11 months.

After our initial meetup at The Roastery by Roj in Chiang Rai, our crew hopped into a couple of cars to head up into the Pangkhon mountains, about 45 minutes from Chiang Rai’s city center. The trip to the mountains is a pleasure - pastoral and scenic for nearly the whole ride. Chiang Rai and its outskirts are impressive, with coffeehouses of all shapes and sizes dotting the landscape in nearly every context possible. Some of them were humble cafes whose largest asset was a seating area overlooking a stream or a deck overlooking a jungle landscape, or cafes a bit removed from the highway, mounted on the edge of a hillside for great views of both the city and countryside. Every cafe seemed to have an espresso machine of some sort, with pour over as the main alternative. Some looked like repurposed huts, while others resembled the high-design cafes we’d expect to see in a major metropolis, and everything in between. Thailand really has taken specialty coffee to heart, and I can see why the majority of their production stays in the domestic market.

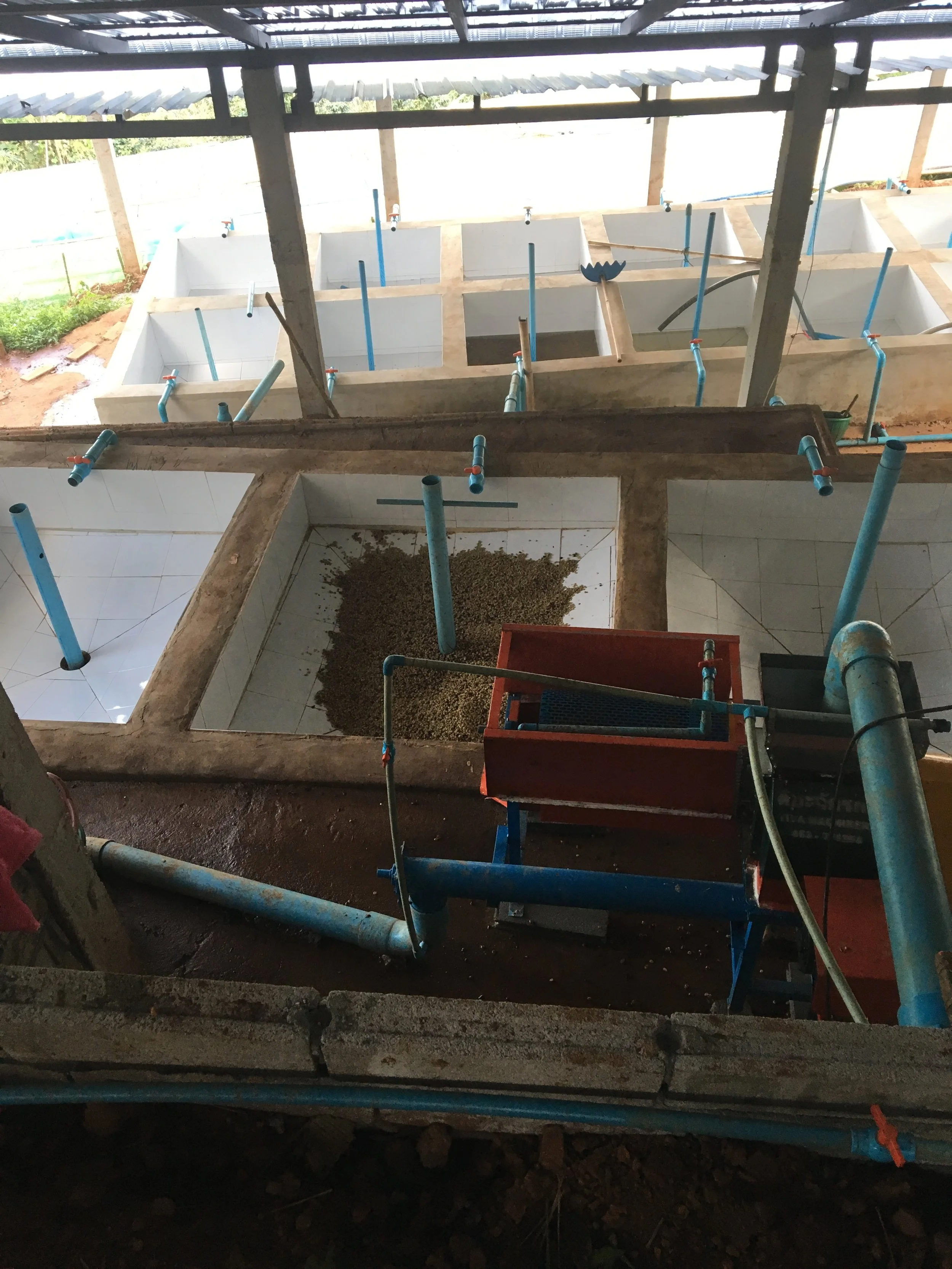

After landing at the mountaintop village, we dropped our luggage and headed straight up to the Doi Pangkhon Wet Mill, owned and operated by five local brothers from the Akha hill tribe. The tribe inhabits the higher elevation mountains spanning a large region - southwest China, eastern Myanmar, western Laos, northwestern Vietnam and northern Thailand. They are known not only for their cultural assets - the intricate embroidery and metal work of their elaborately adorned traditional clothing, their deliciously balanced food - but also for their reverence and stewardship of the mountainous forest environments. They are the only people permitted to cultivate these national preserves, Pangkhon mountains being one of many in the area. Two of the brothers, Apae and Asor, were gracious hosts (though a bit camera-shy), showing us around their wet mill and driving us to a few farms in the area.

Their mill is impressive, with plenty of capacity for modest production of clean, well-processed coffee. A clever build on a hillside allowed them to feed the mill with water from a spring just a bit higher on the slope. A cherry receiving tank sat atop the mill, where floaters are removed and cherry quality observed prior to being released into the pulper, then into one of several tile-lined fermentation tanks. Further sorting can be done here, as can separations based on current needs. These tanks then drain into several more tanks downhill, where they can relieve the volume demands from the primary tanks. Secondary soaking or washing can occur in these lower tanks as well, and they then lead to collection areas for transfer to raised drying beds. The pipes are all interchangeable, which allows for transfer from any one upper tank to the ones below. This modular setup keeps them nimble and allows for experimentation of various types. When we visited, they were doing a couple of lots of “Kenya-style double wash and soak” and some honey processed lots.

That evening, we stayed in modest traditional huts and enjoyed a home-cooked meal at the roadside cafe/homestay, Akha Noi Housing. Our crew was inspired and already talking about the next days’ activities. We roasted samples of this year’s new crop and went to bed happy, full, and fulfilled. Not a bad way to transition from meditation retreat life back into the real world.

The next morning, Kel and I met Fuadi before anyone else woke up for an early stroll to the hilltop for a view of sunrise. Since it was a really cloudy day, we didn’t get to see the sun, but watching the clouds change color on the horizon and seeing the layers of mountains appear from the darkness was a great reward to such an early start.

We chatted about a lot of things - university, Southeast Asian coffee, the village, economic growth, and of course the future as far as we could speculate. The three of us found a lot more in common than differences, and I could feel the beginning of something greater than we could have imagined at that point, or even now. I know for sure that I’ll be seeing Fuadi soon and often.

After sunrise, Fuadi suggested that we stroll around the village and maybe find a cup of coffee somewhere, which sounded perfect.

Our walk into the village led us through the traditional Akha gate, one that welcomes friendly spirits and beings while repelling bad ones. There was a plot of healthy-looking coffee trees just inside. Good signs all around.

We happened across one of Fuadi’s favorite producers, Akor, who consistently delivers some of the village’s best lots. The surprising thing is that this is all done in 40 liter plastic bins, a batch at a time while overlooking a beautiful mountain view. One could easily transport themselves into Akor’s shoes, imagining a romantic life where this peaceful experience is a daily ritual, breathing in crisp, clean mountain air and enjoying an honest living. Of course that would oversimplify and diminish Akor’s life and challenges, and we may have just caught him on a particularly good morning. In fact, it was a pretty great morning overall, and we were reluctant to head back on the road.

We ended up finding some coffee at Ata’s house, where he built a small cafe in his common room and a seating area just outside overlooking the hillside planted with healthy coffee trees. “What a life,” I found myself romanticizing again.

He welcomed us with a very sweet brew of coffee cherry tea, aka Cascara, and proceeded to make a pour over of his latest roast. There were pictures of a couple of friends on the walls as well - Fuadi, Miguel Meza, and Darrin Daniel, who had visited on a buying trip a few years ago and helped to kickstart a new era for the community with a big purchase, advice for improving the crop, and boost of confidence. It was surreal to see buds from so far away adorning the walls of a village cafe, a show of appreciation for the tangible influence and impact that the specialty coffee community brings to the places it touches. It seems as if the community is thriving and growing, with a bright future.

One of the things that really stood out to me was how young the producers I met are - all in their early thirties, educated in nearby big cities, and familiar with current cafe culture. They had tried out the city life, even taking professional level jobs post-graduation and realizing that they could have a better quality of life back home in the village with just as much income. This will be the major takeaway for me on this trip, one that I’ll mull over for some time to come - how to encourage farmers’ children elsewhere to come back and pick up the reins in some capacity, bringing their experience and new skillsets with them to help the family farms grow and thrive. Faudi explained that much of the impetus for these choices among the young coffee farmers can be attributed to King Number 9, Bhumibol Adulyadej, who encouraged agricultural development. I would be remiss if I didn’t also speculate openly here that being paid sustainable prices for their crops contributes directly to their quality of life and their ability to continue doing what they do so well.

Ata’s brew was super tasty, and it was perhaps one of the most charmed mornings I’d had in a long time.

From Doi Pangkhon we headed to the famed Doi Chang area, which I’ll write about next. Stay tuned!